Microsoft Word & Predictive Editing

The frustrations of a dyslexic writer learning that our tools fail us

Writing tools have changed throughout my life. For decades, I benefited. For millions of people, word processors are stealthy assistive devices. With word processors, what I think can now be read by another. What I type can be fixed. And what maybe drafted in error will be highlighted with a marking that says: “Fix me.”

My father, a writer, bought me a typewriter in 1982 for my coming academic adventures. My friend, a prof at a nearby university, helped me secure IBM PC instead. In 2025 money, I paid over $8K for this first-gen desktop computer. Best money ever.

In recent years, the value of these tools has turned against me. I don’t mean that I am a deluded crank fearing that the tools I use daily allow big-IT to steal my copyrighted work to feed AI engines (Maybe I do feel that way, also).

In this case, I mean that the value of the tools pivoted from passive utility to intrusive source of wrong. Thank you, I make my own wrong. I don’t need “wrong” advice to compound my “wrong” efforts. Wrong plus wrong is just more wrong. Therefore, I expect my rather mature word processing system to help me turn wrong to right.

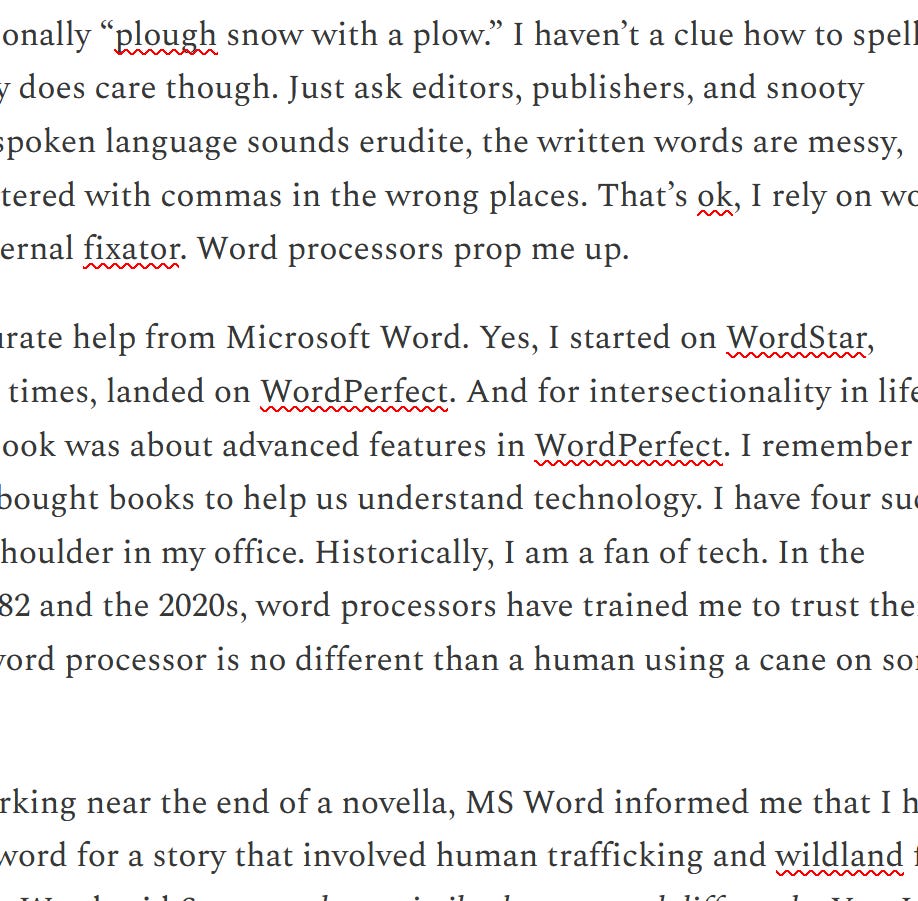

I spell badly. My use of spoken English lands on the erudite mix of Boston and U.K. That means I occasionally “plough snow with a plow.” I haven’t a clue how to spell grey/gray. Somebody does care though. Just ask editors, publishers, and snooty readers. Whilst my spoken language sounds erudite, the written words are messy, inconsistent, and littered with commas in the wrong places. That’s ok, I rely on word processors as an external fixator. Word processors prop me up.

I have trusted Microsoft to provide me with useful, accurate help. Yes, I started on WordStar, upgraded that a few times, then I landed on WordPerfect. And for intersectionality in life, my first published book was about advanced features in WordPerfect. I remember the days when humans bought books to help us understand technology. I have four such books over my left shoulder in my office, each has my name in it. Historically, I am a fan of tech. In the decades between 1982 and the 2022, word processors have trained me to trust them. A dyslexic using a word processor is no different than a human using a cane on sore-knee days.

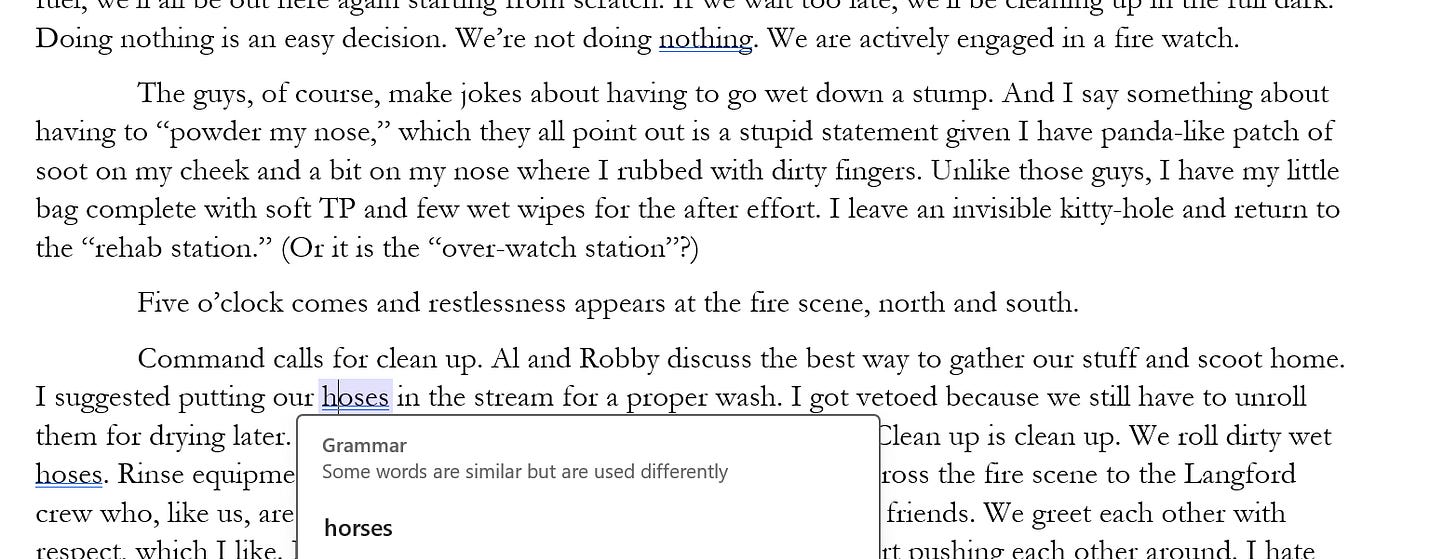

Yesterday, when working near the end of a novella, MS Word informed me that I had selected the wrong word for a story that involved human trafficking and wildland fire fighting in Vermont. Word said Some words are similar but are used differently. Yay. I love that clue. I means that I picked the wrong word in the “piqued, peeked, peaked” set. Or maybe, I muddled my “further/farther.” I bricked the “their/there/they’re” trio, yet again.

I tell Word, “I’m on it.” I click on the underlined word. I learned that Word predicted that I was to “put horses in the stream for a proper wash.” Modern firefighters in Vermont tend not to use horses in the forest while fighting a wildland fire. We do use hoses.

I’ve ridden a hose and ridden a horse, both. Yet, not likely to get them confused. Word suggests that I should have had firefighters “roll dirty wet horses.” Which in rural places comes out just a bit off. In short, I am unlikely to roll a horse. I am likely to roll a hose.

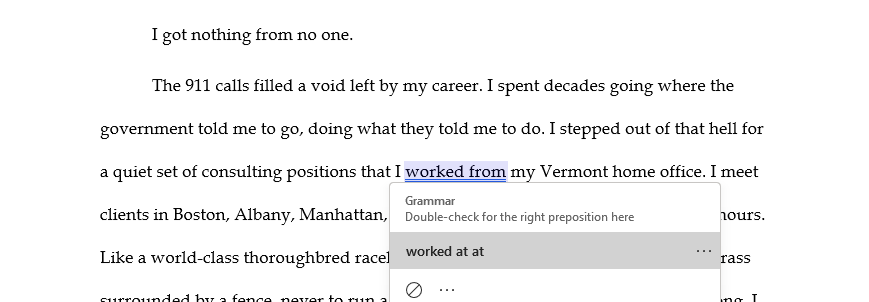

With “WFH” being easily understood and easy to define with common internet search tools, I learned that “work from home” is less supported in Word. I wrote “quiet set of consulting positions that I worked from my Vermont home office,” Word suggested that double-check for the right preposition here. It suggested that I change it to “that I worked at at my Vermont home,” which when I say it aloud, does make sense. You need a bit of a pause. It is ugly, no? Any every editor I know would fuss.

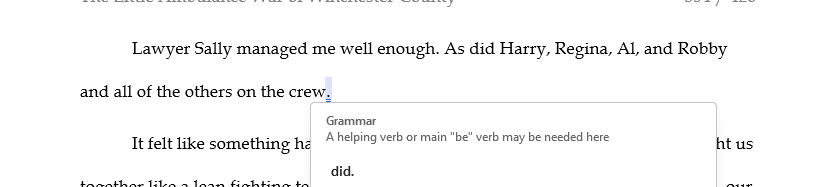

In another passage, Word says, A helping verb or main “be” verb may be needed here did. Apparently, I am to take instructions on writing from that sentence. I ignored Word because I believed that “As did Harry, Regina, A1, Robby and all the others on the crew did,” makes no sense at all. Hum..

In my revenue generating career, I design complex software system. Rather good at it too. In that career I have recently been encouraging folks to be just a little bit wrong. A little bit wrong prompts discussion on how to vector towards right. It’s like a discordant sound in a symphony. People spark to it. Our goal when building system is to model good business practices.

Let people hear something off-key. They then leap in with corrections. The trick works. When discovering systems, wrong is simply a variation of right just as cold is a variant of heat (go annoy a physicist with that question). Offer some information that is slightly wrong. If people are attending to your statements, an enthusiastic conversation will follow.

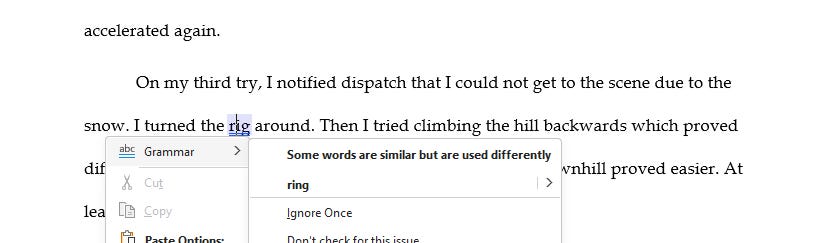

But when driving a “rig” (think: truck), I am rather unlikely to “turn the ring around” (as Word suggests). I’ll agree that “ring” and “rig” include similar letters.

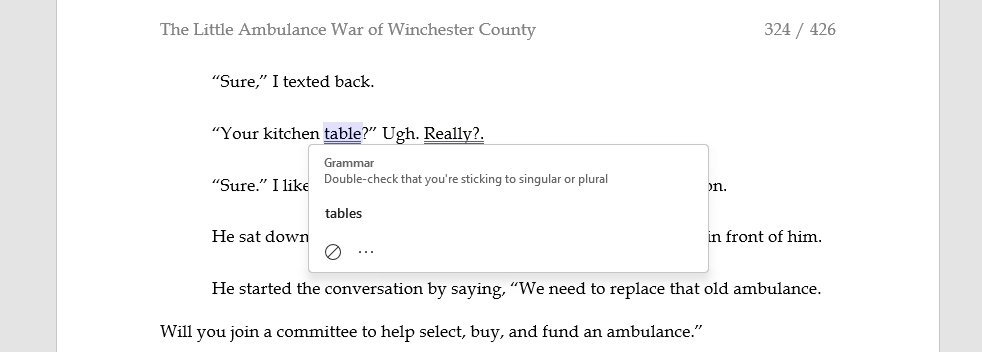

Most kitchen tend to have precisely one table. Word suggests that I replace it with tables.

When I wrote that “Aaron wended north of Harvard Square, I am instructed by Word to write “Aaron ended north of Harvard Square.” There is no comprehension of the writer’s intent. What Word informs me is that using a predictive AI model, most folks would not have used the verb “to wend.” “Wend” is an uncommon verb. Fine. True. I agree, “wend” sounds like “end”. Other than the “w”, the words are not similar. One may argue that “wend” and “end” mean opposite things.

When my narrative described distributing medical gloves, Word disapproved of my description of people “donning” them. Hard to know the difference between Word telling me I am wrong for the use of “donning” or unusual. To test this, I should like to write a sentance were I doff my uniform Let’s see what ye olde Worde thinks about that word “doff.”

When I described that “The New York Yankees creamed Boston,” Word tells me that I ought to have employed the verb “screamed” instead. I admit that screaming does occur when Boston and New York sports teams meet. I doubt MS Word knows that. On that particular July 4th in the 1980s, the Yankees creamed the Red Sox at home.

I regard Microsoft Word as an assistive devices as described within the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Like a cane on bad-knee days, Word augments my ability to write. Regrettably, in the forty-five years since my first hours on a computer, I have learned to trust good software.

What is this change?

I explore this question as a writer, not as a software designer with 45 years of experience. Yes, Microsoft, Google, Adobe are actively pushing us to save confidential and/or copyrighted material on their services (by that I do mean “the cloud”, but “the cloud” is a stupid term for a server that is owned, controlled, and managed by someone else.) Why push us to save our work on their servers? It makes it easier for them to steal the raw text for their large language models, the data source for predictive AI.

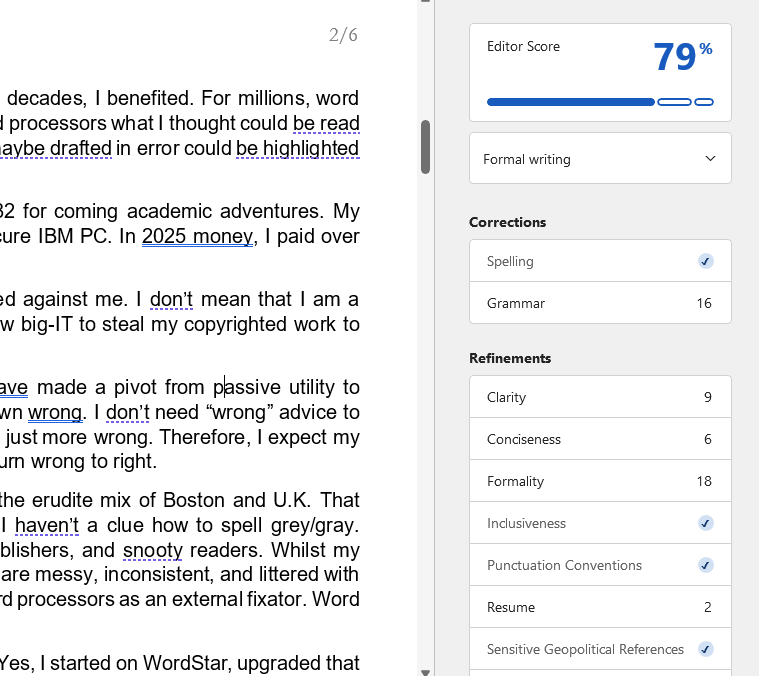

That is the shift in the spelling and grammar checking in Microsoft Word. The shift is “predictive". I predicate my assumption on observations about my writing styles. For IT work, I write technical stuff formally in third person using the past tense. There are four technical books on that shelf behind me with my name in it. Stuff so boring, nobody read it when it was published. When writing fiction, I tend to write first person present tense in a casual, even chatty, manner.

Wanna piss MS Word off, write in first person present tense. I have seen entire pages where the active verb I selected for each sentence earned the dreaded colored underscore. Word has suggested that I selected the wrong verbs in 100% sentences on a page. That is a powerful statement when coming from a tool.

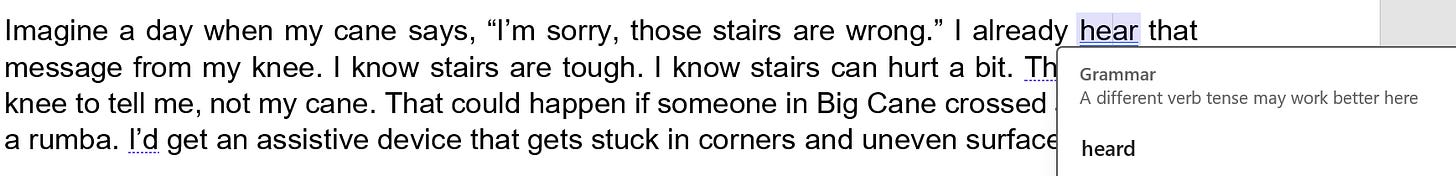

Imagine a day when my cane says, “I’m sorry, those stairs are wrong.” I already hear that message from my knee. I know stairs are tough. I know stairs can hurt a bit. That’s for my knee to tell me, not my cane. That could happen if someone in Big Cane crossed a stick with a rumba. An AI-based walking stick is a horrible idea. I’d operate with an assistive device that gets stuck in corners and uneven surfaces.

Let’s imagine I fix that. Now I have past tense in a present tense paragraph. Word may pause a beat, then tell me my next fixed, then the next item to be fixed. Do I follow the hints to fix it all? I ought to. I am the human operating with a disadvantage. I don’t know the rules well enough to argue. Fine, I’ll go fix it all and do what Word suggests. It is my trusted partner, isn’t it?

The randomness and inconsistency with Word frustrate me. I can learn rules. My fingers have muscle memory for thousands of words. My brain thinks, the fingers execute. I can type words on an ergonomic keyboard that I cannot write with a pen. I don’t T-H-I-N-K words, I type them. Word has been my patient, silent, coach who props me up a bit. It teaches me, well used to teach me. I guess it is still teaching me. Yes, I have to tell it, I like using present tense and first person in formal writing. No, it is not against rules. I have had to write my editors and my publishers now with dumb questions because I can’t find external authority for some of these new “rules.” Over my shoulder is also the “Chicago Manual,” “Strunk & White,” “Eats, Shoots and Leaves.”

Predictive vs Rules

Traditional programmer wrote instruction sets based on rules. A dear friend once said of code, “there is no random code generator in there. 100% of the system’s behavior is driven by your code.” As we explore the early stages of predictive AI, we’re dropping the use of rules leaning more on using AI to predict how a sentance ought to look based on volume of all things ever written by anyone. AI predictions carry no understanding the meaning of words, the feelings that words can evoke. AI predictions simply state that few people would write a sentance involves taking a hose to a stream. Most folks would think of streams and horses. Clearly you can lead a horse to a stream, because that’s been written before.

Rules are hard to understand and hard to program. Instead, if you look at the body of all things written in American English, you can assess how others would have written a sentence. AI-based software will advise on the placement of commas based occurance of commas in other work. Poor little AI has no idea if those rules have been validated by editors, classroom rules, or published style guides. AI-based software involves looking at a volume of other people’s writings and guess at what’s next.

The Contrast

Microsoft Word

I wrote this nonsense in MS Word. On the monitor to my left is the original work complete with Word’s whiny complaints about my writing. In the Word version, I see double underscores. I see dotted underscores. I see a metric about “resume”. This tells me that on resumes, I ought to be precise with numbering. On resumes, I ought to avoid “few,” “some,” “many.” Nice rule. I didn’t know that. Regrettably, not a resume.

An ironic observation is that MS Word highlighted its own phrase for correction and improvement. You clever minx.

Google Chrome

I copied my less-than-perfect prose from Word to Chrome where I am posting it to the Stack of Subs. Here is a screenshot from the editor. In Chrome, my spelling of “plough,” “ok,” “fixator,” and “wildland” are wrong. The camel-case spellings of historic brand names are no longer recognized. Chrome doesn’t like “WordStar” or “WordPerfect.”

Samuel Johnson vs Noah Webster

Two well-intentioned Englishmen had an argument. Noah Webster, after being born a citizen of the United Kingdom, decided that the break between the United States and England created an opportunity to craft an American variant of English with his “blue books” and dictionary. Two centuries later I struggle with their arbitrary decisions. I don’t do that well. But now, the tools I use daily can’t even agree with each other.

Oh well. I’m not given up. I’ll just bitch while writing and hire editors. I can talk with editors. I can listen to editors. That works.

Be sure to run over to my Substack Trowbridge Dispatch for short stories. You may even opt to listen to me read them to you.

I must admit, spelling is my worst enema

This is why we still need human editors.